http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/macroeconomics-principles-v2.0/s12-03-the-federal-reserve-system.html

This is “The Federal Reserve System”, section 9.3 from the book Macroeconomics Principles (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Has this book helped you? Consider passing it on:

Creative Commons supports free culture from music to education. Their licenses helped make this book available to you.

[sidebar: At it again. CREATIVE COMMONS had a DONATION FROM THE GATES' FOUNDATION, substantial, millions of FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM FIAT ?!]

9.3 The Federal Reserve System

Learning Objectives

- Explain the primary functions of central banks.

- Describe how the Federal Reserve System is structured and governed.

- Identify and explain the tools of monetary policy.

- Describe how the Fed creates and destroys money when it buys and sells federal government bonds.

The

Federal Reserve System of the United States, or Fed, is the U.S. central

bank. Japan’s central bank is the Bank of Japan; the European Union has

established the European Central Bank. Most countries have a central

bank. A central bank

performs five primary functions: (1) it acts as a banker to the central

government, (2) it acts as a banker to banks, (3) it acts as a

regulator of banks, (4) it conducts monetary policy, and (5) it supports

the stability of the financial system.

For the

first 137 years of its history, the United States did not have a true

central bank. While a central bank was often proposed, there was

resistance to creating an institution with such enormous power. A series

of bank panics slowly increased support for the creation of a central

bank. The bank panic of 1907 proved to be the final straw. Bank failures

were so widespread, and depositor losses so heavy, that concerns about

centralization of power gave way to a desire for an institution that

would provide a stabilizing force in the banking industry. Congress

passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, creating the Fed and giving it

all the powers of a central bank.

Structure of the Fed

In

creating the Fed, Congress determined that a central bank should be as

independent of the government as possible. It also sought to avoid too

much centralization of power in a single institution. These potentially

contradictory goals of independence and decentralized power are evident

in the Fed’s structure and in the continuing struggles between Congress

and the Fed over possible changes in that structure.

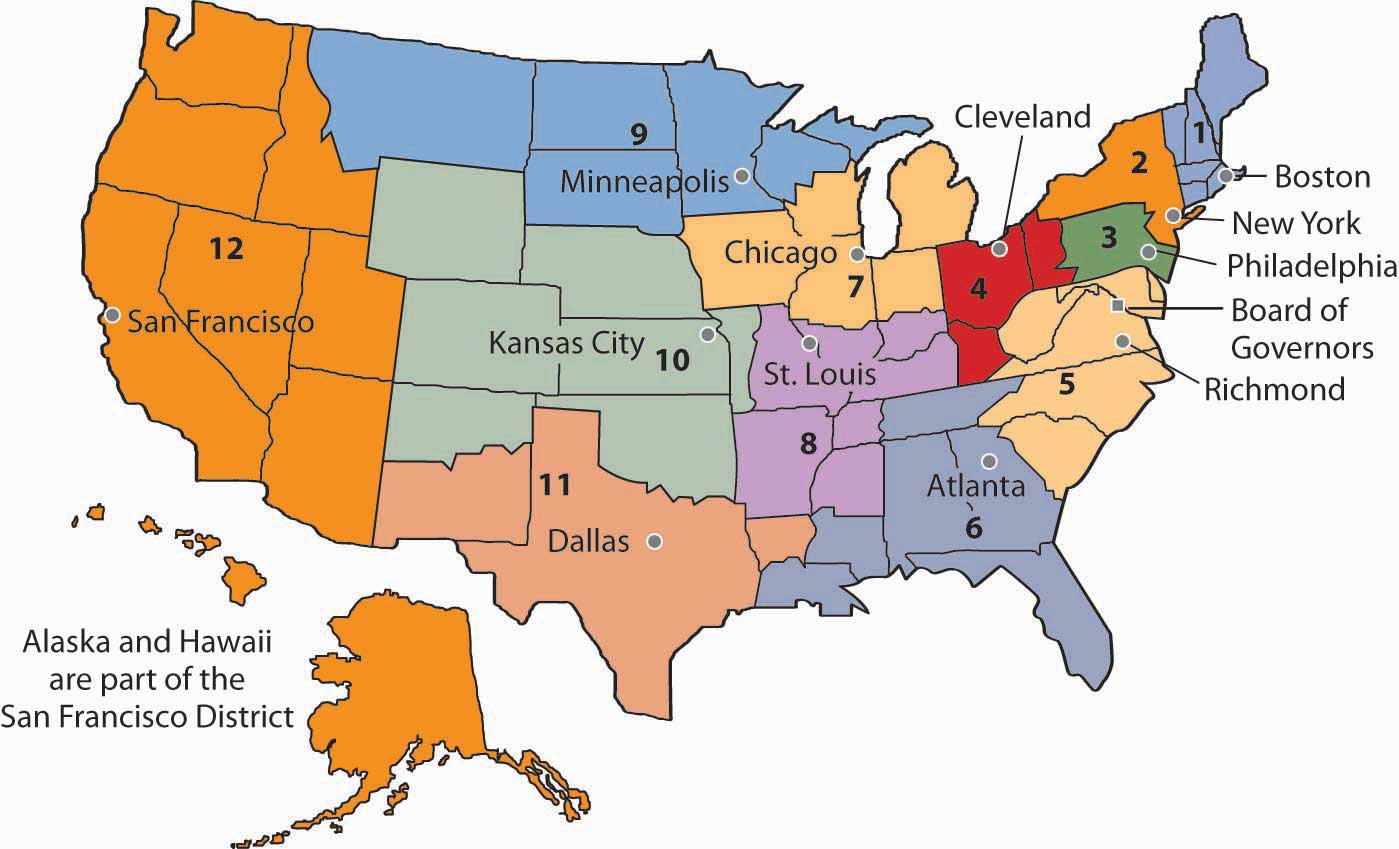

In an effort to decentralize power, Congress designed the Fed as a system of 12 regional banks, as shown in Figure 9.8 "The 12 Federal Reserve Districts and the Cities Where Each Bank Is Located".

Each of these banks operates as a kind of bankers’ cooperative; the

regional banks are owned by the commercial banks in their districts that

have chosen to be members of the Fed. The owners of each Federal

Reserve bank select the board of directors of that bank; the board

selects the bank’s president.

Figure 9.8 The 12 Federal Reserve Districts and the Cities Where Each Bank Is Located

Several

provisions of the Federal Reserve Act seek to maintain the Fed’s

independence. The board of directors for the entire Federal Reserve

System is called the Board of Governors. The seven members of the board

are appointed by the president of the United States and confirmed by the

Senate. To ensure a large measure of independence from any one

president, the members of the Board of Governors have 14-year terms. One

member of the board is selected by the president of the United States

to serve as chairman for a four-year term.

As

a further means of ensuring the independence of the Fed, Congress

authorized it to buy and sell federal government bonds. This activity is

a profitable one that allows the Fed to pay its own bills. The Fed is

thus not dependent on a Congress that might otherwise be tempted to

force a particular set of policies on it. The Fed is limited in the

profits it is allowed to earn; its “excess” profits are returned to the

Treasury.

It

is important to recognize that the Fed is technically not part of the

federal government. Members of the Board of Governors do not legally

have to answer to Congress, the president, or anyone else. The president

and members of Congress can certainly try to influence the Fed, but

they cannot order it to do anything. Congress, however, created the Fed.

It could, by passing another law, abolish the Fed’s independence. The

Fed can maintain its independence only by keeping the support of

Congress—and that sometimes requires being responsive to the wishes of

Congress.

In

recent years, Congress has sought to increase its oversight of the Fed.

The chairman of the Federal Reserve Board is required to report to

Congress twice each year on its monetary policy, the set of policies

that the central bank can use to influence economic activity.

Powers of the Fed

The

Fed’s principal powers stem from its authority to conduct monetary

policy. It has three main policy tools: setting reserve requirements,

operating the discount window and other credit facilities, and

conducting open-market operations.

Reserve Requirements

The

Fed sets the required ratio of reserves that banks must hold relative

to their deposit liabilities. In theory, the Fed could use this power as

an instrument of monetary policy. It could lower reserve requirements

when it wanted to increase the money supply and raise them when it

wanted to reduce the money supply. In practice, however, the Fed does

not use its power to set reserve requirements in this way. The reason is

that frequent manipulation of reserve requirements would make life

difficult for bankers, who would have to adjust their lending policies

to changing requirements.

The

Fed’s power to set reserve requirements was expanded by the Monetary

Control Act of 1980. Before that, the Fed set reserve requirements only

for commercial banks that were members of the Federal Reserve System.

Most banks are not members of the Fed; the Fed’s control of reserve

requirements thus extended to only a minority of banks. The 1980 act

required virtually all banks to satisfy the Fed’s reserve requirements.

The Discount Window and Other Credit Facilities

A

major responsibility of the Fed is to act as a lender of last resort to

banks. When banks fall short on reserves, they can borrow reserves from

the Fed through its discount window. The discount rate is the interest rate charged by the Fed when it lends reserves to banks. The Board of Governors sets the discount rate.

Lowering

the discount rate makes funds cheaper to banks. A lower discount rate

could place downward pressure on interest rates in the economy. However,

when financial markets are operating normally, banks rarely borrow from

the Fed, reserving use of the discount window for emergencies. A

typical bank borrows from the Fed only about once or twice per year.

Instead

of borrowing from the Fed when they need reserves, banks typically rely

on the federal funds market to obtain reserves. The federal funds market is a market in which banks lend reserves to one another. The federal funds rate

is the interest rate charged for such loans; it is determined by banks’

demand for and supply of these reserves. The ability to set the

discount rate is no longer an important tool of Federal Reserve policy.

To

deal with the recent financial and economic conditions, the Fed greatly

expanded its lending beyond its traditional discount window lending. As

falling house prices led to foreclosures, private investment banks and

other financial institutions came under increasing pressure. The Fed

made credit available to a wide range of institutions in an effort to

stem the crisis. In 2008, the Fed bailed out two major housing finance

firms that had been established by the government to prop up the housing

industry—Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Association) and

Freddie Mac (the Federal Home Mortgage Corporation). Together, the two

institutions backed the mortgages of half of the nation’s mortgage

loans.Sam Zuckerman, “Feds Take Control of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac,” The San Francisco Chronicle, September 8, 2008, p. A-1.

It also agreed to provide $85 billion to AIG, the huge insurance firm.

AIG had a subsidiary that was heavily exposed to mortgage loan losses,

and that crippled the firm. The Fed determined that AIG was simply too

big to be allowed to fail. Many banks had ties to the giant institution,

and its failure would have been a blow to those banks. As the United

States faced the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, the

Fed took center stage. Whatever its role in the financial crisis of

2007–2008, the Fed remains an important backstop for banks and other

financial institutions needing liquidity. And for that, it uses the

traditional discount window, supplemented with a wide range of other

credit facilities. The Case in Point in this section discusses these new

credit facilities.

Open-Market Operations

The Fed’s ability to buy and sell federal government bonds has proved to be its most potent policy tool. A bond

is a promise by the issuer of the bond (in this case the federal

government) to pay the owner of the bond a payment or a series of

payments on a specific date or dates. The buying and selling of federal

government bonds by the Fed are called open-market operations.

When the Fed buys or sells government bonds, it adds or subtracts

reserves from the banking system. Such changes affect the money supply.

Suppose

the Fed buys a government bond in the open market. It writes a check on

its own account to the seller of the bond. When the seller deposits the

check at a bank, the bank submits the check to the Fed for payment. The

Fed “pays” the check by crediting the bank’s account at the Fed, so the

bank has more reserves.

The

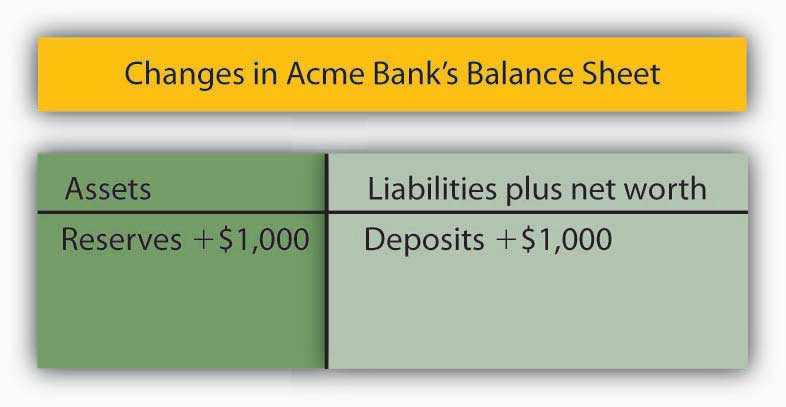

Fed’s purchase of a bond can be illustrated using a balance sheet.

Suppose the Fed buys a bond for $1,000 from one of Acme Bank’s

customers. When that customer deposits the check at Acme, checkable

deposits will rise by $1,000. The check is written on the Federal

Reserve System; the Fed will credit Acme’s account. Acme’s reserves thus

rise by $1,000. With a 10% reserve requirement, that will create $900

in excess reserves and set off the same process of money expansion as

did the cash deposit we have already examined. The difference is that

the Fed’s purchase of a bond created new reserves with the stroke of a

pen, where the cash deposit created them by removing $1,000 from

currency in circulation. The purchase of the $1,000 bond by the Fed

could thus increase the money supply by as much as $10,000, the maximum

expansion suggested by the deposit multiplier.

Figure 9.9

Where

does the Fed get $1,000 to purchase the bond? It simply creates the

money when it writes the check to purchase the bond. On the Fed’s

balance sheet, assets increase by $1,000 because the Fed now has the

bond; bank deposits with the Fed, which represent a liability to the

Fed, rise by $1,000 as well.

When

the Fed sells a bond, it gives the buyer a federal government bond that

it had previously purchased and accepts a check in exchange. The bank

on which the check was written will find its deposit with the Fed

reduced by the amount of the check. That bank’s reserves and checkable

deposits will fall by equal amounts; the reserves, in effect, disappear.

The result is a reduction in the money supply. The Fed thus increases

the money supply by buying bonds; it reduces the money supply by selling

them.

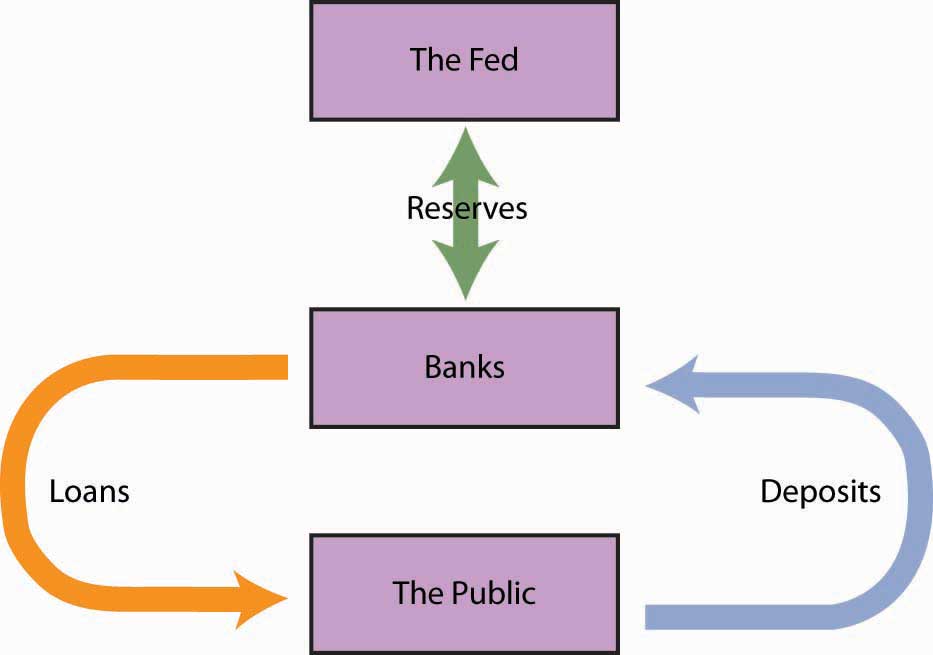

Figure 9.10 "The Fed and the Flow of Money in the Economy"

shows how the Fed influences the flow of money in the economy. Funds

flow from the public—individuals and firms—to banks as deposits. Banks

use those funds to make loans to the public—to individuals and firms.

The Fed can influence the volume of bank lending by buying bonds and

thus injecting reserves into the system. With new reserves, banks will

increase their lending, which creates still more deposits and still more

lending as the deposit multiplier goes to work. Alternatively, the Fed

can sell bonds. When it does, reserves flow out of the system, reducing

bank lending and reducing deposits.

Figure 9.10 The Fed and the Flow of Money in the Economy

Individuals and firms (the public) make

deposits in banks; banks make loans to individuals and firms. The Fed

can buy bonds to inject new reserves into the system, thus increasing

bank lending, which creates new deposits, creating still more lending as

the deposit multiplier goes to work. Alternatively, the Fed can sell

bonds, withdrawing reserves from the system, thus reducing bank lending

and reducing total deposits.

The

Fed’s purchase or sale of bonds is conducted by the Open Market Desk at

the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, one of the 12 district banks.

Traders at the Open Market Desk are guided by policy directives issued

by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC consists of the

seven members of the Board of Governors plus five regional bank

presidents. The president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank serves as

a member of the FOMC; the other 11 bank presidents take turns filling

the remaining four seats.

The

FOMC meets eight times per year to chart the Fed’s monetary policies.

In the past, FOMC meetings were closed, with no report of the

committee’s action until the release of the minutes six weeks after the

meeting. Faced with pressure to open its proceedings, the Fed began in

1994 issuing a report of the decisions of the FOMC immediately after

each meeting.

In

practice, the Fed sets targets for the federal funds rate. To achieve a

lower federal funds rate, the Fed goes into the open market buying

securities and thus increasing the money supply. When the Fed raises its

target rate for the federal funds rate, it sells securities and thus

reduces the money supply.

Traditionally,

the Fed has bought and sold short-term government securities; however,

in dealing with the condition of the economy in 2009, wherein the Fed

has already set the target for the federal funds rate at near zero, the

Fed has announced that it will also be buying longer term government

securities. In so doing, it hopes to influence longer term interest

rates, such as those related to mortgages.

Key Takeaways

- The Fed, the central bank of the United States, acts as a bank for other banks and for the federal government. It also regulates banks, sets monetary policy, and maintains the stability of the financial system.

- The Fed sets reserve requirements and the discount rate and conducts open-market operations. Of these tools of monetary policy, open-market operations are the most important.

- Starting in 2007, the Fed began creating additional credit facilities to help stabilize the financial system.

- The Fed creates new reserves and new money when it purchases bonds. It destroys reserves and thus reduces the money supply when it sells bonds.

Try It!

Suppose the Fed sells $8 million worth of bonds.

- How do bank reserves change?

- Will the money supply increase or decrease?

- What is the maximum possible change in the money supply if the required reserve ratio is 0.2?

Case in Point: Fed Supports the Financial System by Creating New Credit Facilities

Well

before most of the public became aware of the precarious state of the

U.S. financial system, the Fed began to see signs of growing financial

strains and to act on reducing them. In particular, the Fed saw that

short-term interest rates that are often quite close to the federal

funds rate began to rise markedly above it. The widening spread was

alarming, because it suggested that lender confidence was declining,

even for what are generally considered low-risk loans. Commercial paper,

in which large companies borrow funds for a period of about a month to

manage their cash flow, is an example. Even companies with high credit

ratings were having to pay unusually high interest rate premiums in

order to get funding, or in some cases could not get funding at all.

To

deal with the drying up of credit markets, in late 2007 the Fed began

to create an alphabet soup of new credit facilities. Some of these were

offered in conjunction with the Department of the Treasury, which had

more latitude in terms of accepting some credit risk. The facilities

differed in terms of collateral used, the duration of the loan, which

institutions were eligible to borrow, and the cost to the borrower. For

example, the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) allowed primary

dealers (i.e., those financial institutions that normally handle the

Fed’s open market operations) to obtain overnight loans. The Term

Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) allowed a wide range of

companies to borrow, using the primary dealers as conduits, based on

qualified asset-backed securities related to student, auto, credit card,

and small business debt, for a three-year period. Most of these new

facilities were designed to be temporary. Starting in 2009 and 2010, the

Fed began closing a number of them or at least preventing them from

issuing new loans.

The

common goal of all of these various credit facilities was to increase

liquidity in order to stimulate private spending. For example, these

credit facilities encouraged banks to pare down their excess reserves

(which grew enormously as the financial crisis unfolded and the economy

deteriorated) and to make more loans. In the words of Fed Chairman Ben

Bernanke:

“Liquidity

provision by the central bank reduces systemic risk by assuring market

participants that, should short-term investors begin to lose confidence,

financial institutions will be able to meet the resulting demands for

cash without resorting to potentially destabilizing fire sales of

assets. Moreover, backstopping the liquidity needs of financial

institutions reduces funding stresses and, all else equal, should

increase the willingness of those institutions to lend and make

markets.”

The

legal authority for most of these new credit facilities came from a

particular section of the Federal Reserve Act that allows the Board of

Governors “in unusual and exigent circumstances” to extend credit to a

wide range of market players.

Sources:

Ben S. Bernanke, “The Crisis and the Policy Response” (Stemp Lecture,

London School of Economics, London, England, January 13, 2009); Richard

DiCecio and Charles S. Gascon, “New Monetary Policy Tools?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Monetary Trends, May 2008; Federal Reserve Board of Governors Web site at http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/default.htm.

Answer to Try It! Problem

- Bank reserves fall by $8 million.

- The money supply decreases.

- The maximum possible decrease is $40 million, since ∆D = (1/0.2) × (−$8 million) = −$40 million.

http://www.theartof12.blogspot.com/2014/07/federal-reserve-private-jewish-bank.html

Money isn't and yet every so called U.S. Citizen not only pays interest on the CRIMINAL FRAUD, indeed get to be killed just like that for the killing fun.

ReplyDelete