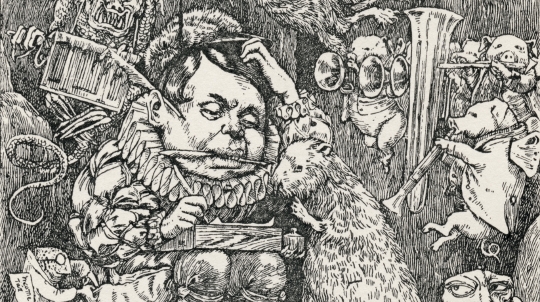

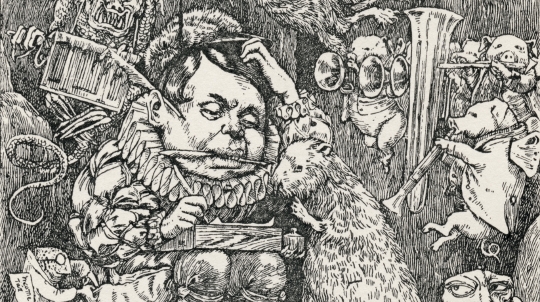

Lewis Carroll and The Hunting of the Snark

In 1876

Lewis Carroll published by far his longest poem – a fantastical epic

tale recounting the adventures of a bizarre troupe of nine tradesmen and

a beaver. Carrollian scholar, Edward Wakeling, introduces The Hunting

of the Snark.

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

- See more at: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/02/22/lewis-carroll-and-the-hunting-of-the-snark/#sthash.iIAhtEc4.dpuf

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

Lewis Carroll and The Hunting of the Snark

In 1876

Lewis Carroll published by far his longest poem – a fantastical epic

tale recounting the adventures of a bizarre troupe of nine tradesmen and

a beaver. Carrollian scholar, Edward Wakeling, introduces The Hunting

of the Snark.

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

- See more at: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/02/22/lewis-carroll-and-the-hunting-of-the-snark/#sthash.iIAhtEc4.dpuf

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

Lewis Carroll and The Hunting of the Snark

In 1876

Lewis Carroll published by far his longest poem – a fantastical epic

tale recounting the adventures of a bizarre troupe of nine tradesmen and

a beaver. Carrollian scholar, Edward Wakeling, introduces The Hunting

of the Snark.

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

- See more at: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/02/22/lewis-carroll-and-the-hunting-of-the-snark/#sthash.iIAhtEc4.dpuf

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

Lewis Carroll and The Hunting of the Snark

In 1876

Lewis Carroll published by far his longest poem – a fantastical epic

tale recounting the adventures of a bizarre troupe of nine tradesmen and

a beaver. Carrollian scholar, Edward Wakeling, introduces The Hunting

of the Snark.

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

- See more at: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/02/22/lewis-carroll-and-the-hunting-of-the-snark/#sthash.iIAhtEc4.dpuf

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

In 1876 Lewis Carroll published by far his longest poem – a fantastical epic tale recounting the adventures of a bizarre troupe of nine tradesmen and a beaver. Carrollian scholar, Edward Wakeling, introduces The Hunting of the Snark.

Although best known as the author of *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865) and *Through the Looking-Glass* (1871), Lewis Carroll – the pen-name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford – was also an avid reader and writer of poetry. He greatly enjoyed the poems of Victorian writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Christina Rossetti. His own poems were varied – some just humorous nonsense, some filled with hidden meanings, and some serious poems about love and life. Probably his best known is called “Jabberwocky,” with its opening line of “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves…”, and its many invented words, some that have now entered the English language, such as “chortle” and “galumph”. Such nonsense verse is as popular now as it was when first published. His more serious poetry, it must be admitted, is generally inferior to his humorous verse and often over sentimental. Between 1860 and 1863 he contributed a dozen or more poems to College Rhymes, a pamphlet issued each term to members of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and which, for a time, he edited. In 1869, he compiled a book of poems, many of which he had already published elsewhere but now issued in revised form, together with one main new poem, which gives its title to the book, *Phantasmagoria*.

One particular poem stands out from all the others that Carroll wrote. It has inspired parodies, continuations, musical adaptations, and a wide variety of interpretations. It is an epic nonsense poem written at a time when Carroll was struggling with his religious beliefs following the serious illness of his cousin and godson, Charlie Wilcox, who eventually died from tuberculosis. Although the poem concerns death and danger, it is filled with humour and whimsical ideas. Strangely, it was written backwards. After a night nursing his cousin, Carroll went for a long walk over the hills near Guildford, and a solitary line of verse came into his head – “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see!” The rest of the stanza, the last in the poem, came to him a few days later. Over a period of six months, the rest of poem was composed, ending up as 141 stanzas in 8 sections that Carroll called “fits.”

- See more at: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/02/22/lewis-carroll-and-the-hunting-of-the-snark/#sthash.iIAhtEc4.dpuf

|

| I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think. Was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is 'Who in the world am I?' Ah, that's the great puzzle! |

[SIDEBAR#1: Lewis Carroll was also a photographer. What a world he would have produced for children!]

>> http://math.ucdenver.edu/~wcherowi/courses/m4010/s08/erdodgson.pdf

[SIDEBAR#2: Lewis Carroll understood the unseen and seen?']

I charm in vain: for never again

All keenly as my glance I bend,

Will memory, goddess coy,

Embody for my joy

Departed days, nor let me gaze

On thee! My Fairy Friend!

Yet could thy face, in mystic grace,

A moment smile on me, ‘twould send

Far-darting rays of light

From Heaven athwart the night,

By which to read in every deed

Thy spirit, sweetest Friend!

So may the stream of Life’s long dream

Flow gently onward to its end,

With many a floweret gay

A-down its willowy way:

May no sigh vex, No care perplex

My loving little Friend

All keenly as my glance I bend,

Will memory, goddess coy,

Embody for my joy

Departed days, nor let me gaze

On thee! My Fairy Friend!

Yet could thy face, in mystic grace,

A moment smile on me, ‘twould send

Far-darting rays of light

From Heaven athwart the night,

By which to read in every deed

Thy spirit, sweetest Friend!

So may the stream of Life’s long dream

Flow gently onward to its end,

With many a floweret gay

A-down its willowy way:

May no sigh vex, No care perplex

My loving little Friend

How did GOLDMAN SACHS get hold of the stories told to adults and children & WOW the algorithms aren't at all what would-could-should be in studying the great mathematicians such as Lewis Carroll, Et Al

ReplyDelete